This entry is part of the 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks series. This week’s prompt is Map It Out. (To see other posts in this series, view my 52 Ancestors in 2019 index.)

I love using maps for genealogy. Most of my ancestors were farmers who owned land across the southern United States, so my research is never complete without land patent and deed searches. Mapping my ancestors’ land can uncover neighbors’ names who quite often turn out to be family. Graphing the land on a map also shows me proximity to other counties and parishes, providing clues to jurisdictions where additional records may be found.

This week I chose a branch of my family I haven’t explored very much — just for the academic exercise of graphing a parcel of land and seeing what resulted. I chose my earliest known Ingram ancestor, my 3x-great-grandfather Jackson P. Ingram. And the result was discovering a veteran in my family I never knew existed from a war I barely knew existed.

Jackson P. Ingram was probably born between 1812 and 1817, in Georgia. I know very little about Jackson; all my data comes from U.S. censuses:

In 1850, Jackson lived in Western Division, Chickasaw County, Mississippi, with his inferred wife Elizabeth, and three children: Nancy, age 5; Green, age 3, and Virgin, 2 months. By 1860, Jackson and Elizabeth were in Calhoun County, Mississippi, with even more children:

- Nancy, age 15

- John, age 12 (probably the same child “Green” in 1850)

- Virgin, age 9

- Abram, age 7

- Sarah, age 5

- Joshua, age 2 (from whom I descend)

Did the family move? A look at one of my favorite map tools, MapofUs.org, illustrated historical county boundaries. In 1852, the western half of Chickasaw County became Calhoun. It was most likely the county lines that moved — not the Ingram family.

I next checked the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office for land patents belonging to Jackson Ingram — success! I got two results for Jackson, both in Calhoun County.

MS1460__.340 – State Volume Patent

Certificate No. 31617

Issue Date: 1 Sep 1846

Patentee: “Jackson P. Ingram of Chickasaw County, Mississippi”

Meridian: Choctaw

Township-Range: 22N-10E

Section: 32

Aliquots: SW1/4

MW-0660-163 – Military Warrant

Warrant No. 66873

Issue Date: 5 May 1853

Patentee: “Jackson P. Ingram, private in Captain Sharp’s Company, Alabama Militia, Florida War”

Meridian: Choctaw

Township-Range: 22N-10E

Section: 32

Aliquots: NE1/2 SE1/4

The first land patent was a result of Jackson improving and then purchasing the land; however, the second was much more interesting. Jackson actually received this land for his military service. It seems he was a veteran of the Florida War — part of the conflicts commonly known as the Indian Wars.

Digitized personnel records for the Indian Wars aren’t as readily accessible online as Revolutionary or Civil War records. But Fold3 did have an index of bounty-land warrant applications. This index indicated Jackson’s service year was 1836, and his military service unit was Alabama Militia, Capt. Sharp, Col. McLenore. Jackson’s service record index card also said he was part of Webb’s Battalion in this unit. These additional clues may help me find more details about Jackson’s service, but I suspect the most helpful information will come from studying the history of these conflicts rather than finding specific records about my ancestor.

In 1836 in Alabama, conflict arose between the Creek Nation and the U.S. Army and Alabama and Georgia militias. White settlers had been cheating the native peoples out of their lands for decades, ignoring treaties the Creek had made with the federal government. The conflict was primarily in areas along the Chattahoochee River in present-day Chambers, Macon, Pike, Lee, Russell, and Barbour counties. As the Creeks resisted, President Andrew Jackson established a policy of forced removal to Indian Territory in what is now the state of Oklahoma. The U.S. Army and the Alabama and Georgia militias suppressed Creek uprisings, rounded up families, and forced them into concentration camps. The Creek were then marched out of their ancestral lands along a 750-mile route sometimes known as the “Creek Trail of Tears.”

Was Jackson’s military service involved with the forced removal of the Creeks? I’m not sure yet. But the area of conflict and involved counties do give me an area to comb for earlier records about Jackson. I can also contact the National Archives to obtain Jackson’s entire service record as well as his bounty land application. These documents could contain key information about Jackson’s birth date and place, possibly filling in a huge gap in this part of my family tree.

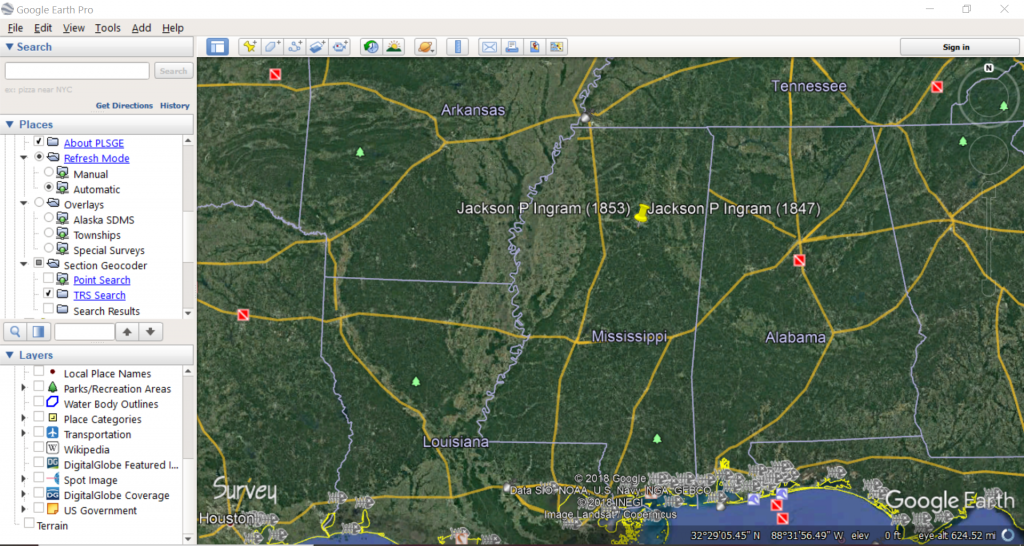

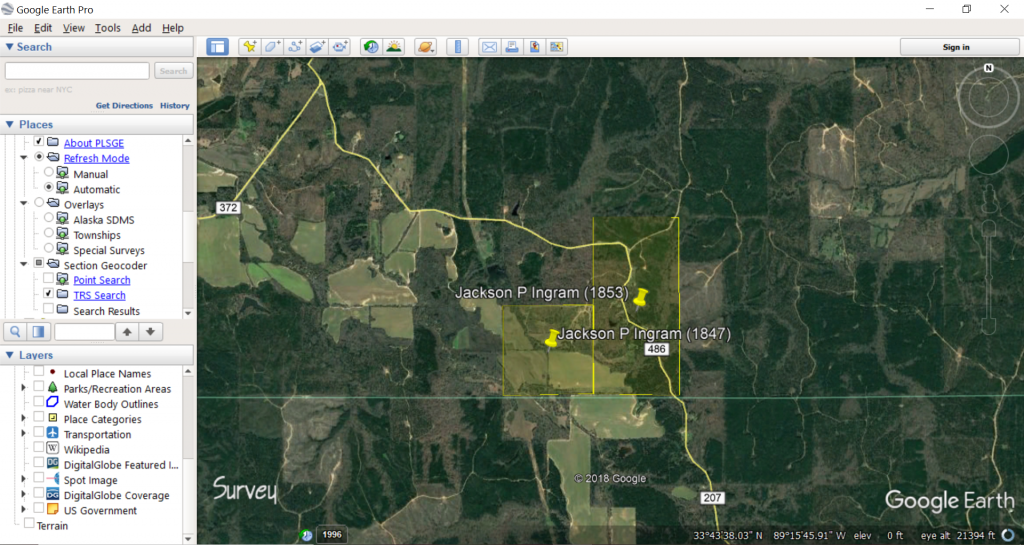

In the mean time, I mapped the land Jackson patented and the adjoining land he received for his military service, totaling approximately 240 acres along the Calhoun-Webster county line in north central Mississippi.

using PLSS for Google Earth Pro (Earth Survey)

using PLSS for Google Earth Pro (Earth Survey)

I use a free application from Earth Survey to graph land patents in states that are part of the Public Land Survey System. The tool is called PLSS in Google Earth (PLSGE) and can be downloaded and launched within Google Earth Pro — the desktop application, not the online maps. PLSGE adds layers to Google Earth Pro, including layers that show township, range, and section lines across all PLSS states. Once I have this layer on top of my map, I find the desired location and draw transparent polygons to indicate a specific parcel of land. It’s super useful for translating a text description of a specific property to envisioning it in the real world. Google Earth Pro also has historic and current satellite images, meaning I can usually see captured images of the land from the past 15 – 20 years.

I am also a big fan of HistoryGeo’s First Landowners Project for mapping land patents, but this subscription service is only available to me at my local genealogy library. I can use PLSGE for free at home and also map land deeds that are later sales — not just the first owner of the property.

Maps are fun, especially when they help you learn something new about an ancestor.